RenewAire Energy Recovery Ventilator. Image courtesy of RenewAire.

By George Harvey

Sometimes it seems builders and architects have settled into a chorus, all chanting the same thing. Whether the current verse is about LEED Platinum buildings, achieving zero net energy or better, or passive house standards, the chorus seems to be, “Plug every little air leak.”

While it is certainly true that air infiltration can ruin a building’s efficiency, it is equally true that poor ventilation produces stale air, with reduced oxygen levels and high levels of humidity, carbon dioxide, and other pollutants. Good balanced ventilation requires that fresh air be brought into a building from outside, and stale air from inside the building be expelled.

One set of building regulations we know of requires air equal to half a home’s volume be changed every hour. In a 1,500-square-foot home, this might be about 1.7 cubic feet per second. It seems hard to imagine that so much air could pass through a building without having negative effects on its heating efficiency.

An obvious solution to this problem is to use the heat of the stale air being expelled from the building to warm up fresh air coming in. The simplest systems that do this are called heat recovery ventilators (HRVs).

To picture how this works, imagine an HRV built by putting a long piece of four-inch stovepipe inside an equally long piece of six-inch stovepipe. There is no insulation between the two, but the whole is insulated on the outside. Cold, fresh air will come into a house through one pipe, and warm, stale air will go out through the other. Fans are rigged to force air movement. The cold incoming air is heated by the warm outgoing air, and efficiencies in such a rig can be surprisingly high, if the pipes are long enough.

There are problems with all such overly simple HRVs. One is that they do not address issues of humidity. Water in the moisture-laden warm air will condense as it cools in the HRV, and this needs to be dealt with or the unit may leak or corrode, leading to contamination of incoming air and possibly increased humidity in the home. These conditions can provide for growth of bacteria and mold, leading to issues ranging from health problems to structural damage of the building.

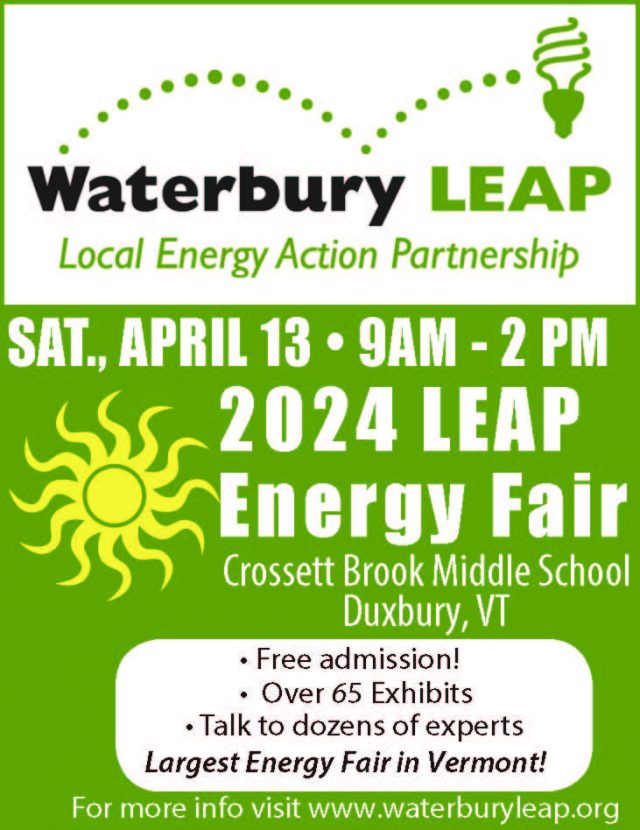

The good news is that more carefully engineered systems are available. These are the energy recovery ventilators (ERVs) such as those offered by RenewAire. Readers may remember an article on RenewAire in our June issue, in which we took a look at the company’s environmentally conscious approaches to manufacturing.

An ERV is a system that not only recovers heat that would otherwise be lost, but also addresses issues of humidity. In the winter, the humidity of outgoing air is passed to what is drier, colder air coming in just as the heat is. In the summer, the operation goes in the opposite direction, with incoming humidity being captured in the drier air going out. Any pollutants that would otherwise build up in the inside air are moved outside at the same time. This all can happen without any chemicals or moving parts, aside from the fans used to move the air, if a good unit is chosen.

The result of all these things is that it is now possible to have a building that is highly energy efficient and also has very healthy air. Homes can have the even temperatures of highly efficient buildings, and at the same time they can be free of the health issues relating to restricted ventilation.

There is a set of links to videos showing how an ERV works, the advantages of an ERV system, and other interesting topics at the home page of RenewAire’s website, www.renewaire.com.

Leave a Reply