Trainers and attendees carry a solar panel during a rooftop solar training in Highland Park, MI. (Nick Hagen)

Pamela Worth

In the early 20th century, Ford Motor Company opened the world’s first moving assembly line in Highland Park, Michigan. The auto industry fueled the city’s economy for generations, transforming a rural town into a busy city. However, when the auto industry took hits, so did Highland Park. Today, the city’s roughly 10,000 residents—of whom about 46 percent live at or below the poverty line—are interested in a more collaborative model of innovation and grassroots transformation: building resilience within their community through “energy sovereignty.”

“The traditional model of communities paying utility companies for power and people not having much of a say in it isn’t working for us,” says Shimekia Nichols, executive director of the Highland Park–based nonprofit Soulardarity. “Like residents in many communities, Highland Parkers want the ability to choose clean, locally generated power and keep more of the money we spend for electricity circulating in our neighborhoods.”

Soulardarity and the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) set out to explore how Highland Park might realize its vision of a locally controlled, equitable, and clean energy system—a system powered by resilient and affordable resources like solar and energy efficiency, owned by residents and businesses.

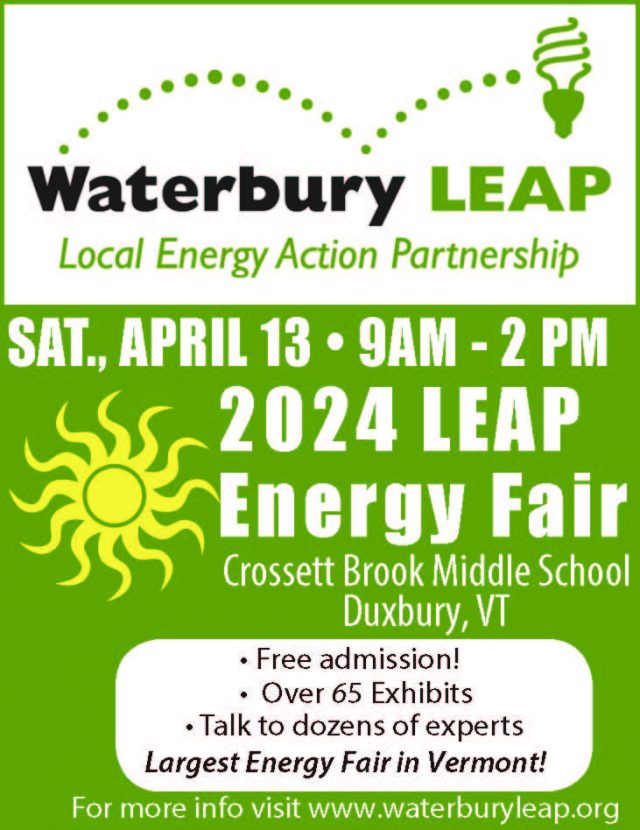

A MODEL FOR MANY COMMUNITIES

Soulardarity was founded ten years ago after the local electrical utility serving southeast Michigan, DTE Energy, didn’t just turn off but removed more than two-thirds of the community’s streetlights as it struggled to pay high electricity bills. Since then, Soulardarity has worked to install solar-powered streetlights, help residents improve energy efficiency in their homes, and advocate for a just and equitable energy system. In conversations with UCS Campaign Coordinator Camilo Esquivia-Zapata, Senior Bilingual Energy Analyst Paula García, Senior Midwest Energy Analyst James Gignac, and Energy Organizing Manager Edyta Sitko, Soulardarity members and city residents turned to Soulardarity’s Blueprint for Energy Democracy, and a previous UCS analysis conducted in partnership with a Boston neighborhood, to begin charting Highland Park’s path toward energy sovereignty.

At a solar training at Parker Village in May 2021, Highland Park residents learn about how rooftop solar projects connect to a home’s electricity meter. (Nick Hagen)

“We wanted to map out what a local future of clean energy could look like for Highland Park,” says Gracie Wooten, a Highland Parker and Soulardarity member. “Our vision is strong, but we wanted data and modeling to back up our case to residents, officials, and utilities that the vision is real and achievable.”

Using information provided by Soulardarity’s experts and through other research—and applying modeling software called Hybrid Optimization of Multiple Energy Resources (HOMER)—Gignac, Sitko, UCS Energy Modeler Youngsun Baek, and the rest of the team created a comprehensive analysis that shows how energy efficiency and clean energy generated locally by rooftop solar panels installed on homes and businesses, larger solar installations, and a community water and energy resource center to process wastewater and turn it into electricity could meet 100 percent of Highland Park’s electricity demand. The full analysis, presented in the report Let Communities Choose: Clean Energy Sovereignty in Highland Park, Michigan, can be found at www.ucsusa.org/resources/let-communities-choose-clean-energy.

Sitko says Soulardarity is running with the results. “They’ve been engaged in conversations with city officials around their goals,” she says. “And using the analysis as a pressure point for that. We wanted to help continue and contribute to the great work they’re doing.”

REDUCING POLLUTION, IMPROVING SERVICE, AND LOWERING COSTS

As the recent UCS report A Transformative Climate Action Framework makes clear, we cannot achieve the clean energy transition we so desperately need without accounting for the needs of all kinds of communities in the United States. For example, because of systemic racism, fossil fuel generators that burn coal and gas are disproportionately sited in or near low-income communities and communities of color, contaminating the local environment and posing health risks for residents. Shifting to clean energy would not only drive down carbon emissions but also right this injustice.

In Highland Park, which University of Michigan researchers have identified as particularly vulnerable to air pollution from nearby power plants and factories, residents are paying the price—and not just in negative health outcomes. According to well-established economic research, energy costs should make up six percent or less of a household’s income. But in Michigan, households with annual incomes similar to Highland Park’s median income pay 18 to 33 percent of their incomes, according to Soulardarity calculations. This inequity is partly driven by aggressive increases in DTE Energy’s residential electricity rates. In addition, some Highland Parkers have reported multiple days of outages over the past year.

“It’s not hard to understand why cities like Highland Park would demand safe, resilient, clean, affordable, and community-driven systems,” Gignac says. “Energy sovereignty should be a core building block as we seek not only to decarbonize our power generation, but also to address the ways in which electricity production and distribution are unjust and inequitable.”

“This is some of the most meaningful work I’ve done with UCS,” says Sitko. “To make this point and prove that locally produced and owned clean energy is possible for communities like Highland Park. Now let’s make these changes happen.”

Pamela Worth is senior writer in the Communications department at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Leave a Reply