Debra Heleba

Growing vegetables in raised beds has become popular among gardeners, especially here in New England as this system helps the soil warm quickly in the spring and allows for good drainage. Jennifer Wilhelm of Fat Peach Farm in Madbury, New Hampshire sought to learn the potential of using permanent raised beds on a commercial farm scale through a two-year research project.

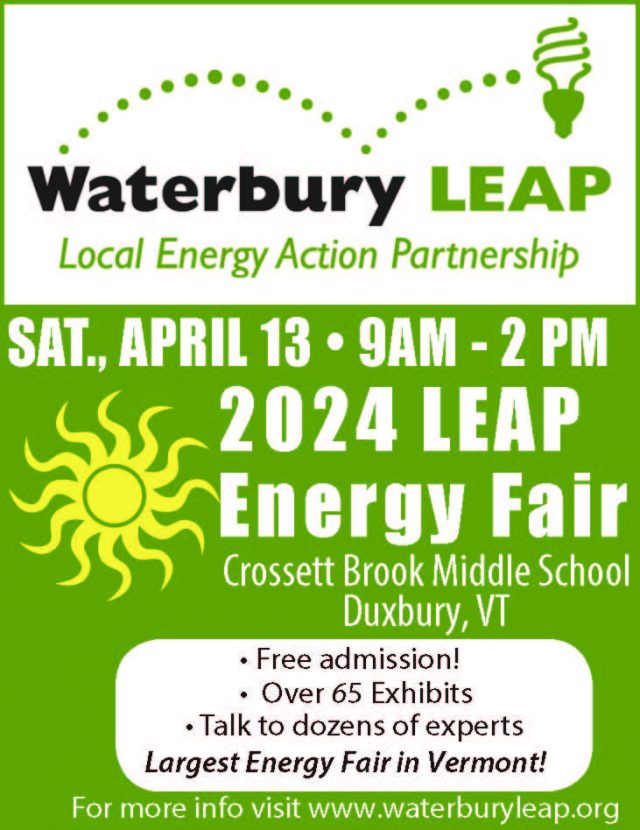

Jennifer Wilhelm of Fat Peach Farm in Madbury, New Hampshire conducted a Northeast SARE Farmer Grant research project on a no-till permanent raised bed system for small-scale mixed vegetable operations. Photo credit: Carol Delaney.

Wilhelm and her family started their one-acre farm in 2013. The farm’s marginal soils compelled them to establish a no-till permanent raised bed system for their organic mixed vegetable operation. Beds were built by covering sod with hardwood chips about four inches deep and thirty-two inches wide with eighteen inches between the rows. Compost was laid on top.

Wilhelm rotates crops during the season and plants cover crops at the season’s end to add organic matter and stabilize the beds. Black tarps cover the rows three weeks before they are planted to further warm the soil and kill any surface weeds.

Since little is known about the productivity of no-till permanent raised beds in commercial settings, Wilhelm received a Farmer Grant from the Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program (SARE) for a two-year experiment to investigate the system’s weed suppression, soil health and yield potential.

Wilhelm researched the effectiveness of permanent raised beds for suppressing weeds. She conducted a weed-bank study where weeds were collected and identified weekly and soil cores were sent to the University of New Hampshire Greenhouse to assess weed germination that may have been suppressed by the system. The study revealed that the farm had a high diversity of weeds but fortunately a low abundance of them. Wilhelm also monitored time spent weeding and calculated that about 3% of total farm time was spent weeding, costing the farm an average of $547.50 per farm laborer per season.

To evaluate soil health, Wilhelm turned to Cornell University’s Comprehensive Assessment of Soil Health. The assessment goes beyond a standard soil test and evaluates soil health dimensions including physical factors (aggregate stability, etc.) biological factors (organic matter and soil respiration), and chemical factors (soil pH, phosphorus levels and other nutrients). Test results showed that all soil health factors on the farm’s growing areas were optimal. The beds had high organic matter suggesting that the system may effectively increase water holding capacity and prevent run-off. However, high levels of phosphorus were detected in both years of the study. Since excess phosphorus can limit plant uptake of nutrients and can negatively affect water quality, this discovery showed Wilhelm that she needed to change the farm’s fertility management practices. In addition, Wilhelm observed that first year plantings did not perform well, presumably because the wood chips robbed nitrogen from the soil, inhibiting plant growth.

Onions grow in no-till permanent raised beds at Fat Peach Farm. The beds were created with compost laid on top of hardwood chips. Photo credit: Carol Delaney.

For growers interested in this system, Wilhelm suggests, “Collect soil samples before beginning to get a baseline to compare with future samples. If using a carbon layer under rows, understand that it can take a full year for the system to establish the soil microbial community as well as to come to an equilibrium of the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, which all can negatively affect yields. We suggest converting a portion of the total growing space and sowing a cover crop the first year, then rotating in cash crops until the desired area is converted.”

Wilhelm also looked at the system’s yield potential and concluded that after plots were established, permanent raised beds produce consistent yields.

The research confirmed for Wilhelm that no-till, permanent raised beds can be a viable system for small-scale growers. She said, “The grant allowed us to collect data to tell a more complete story about the farm management system we use here. The data gave us confidence that the [permanent raised bed] system works well for building soil organic matter, producing high yields (after year one), and most impressively suppressing the weed seed bank.” Full research results for Wilhelm’s project can be found at https://projects.sare.org/sare_project/fne18-914/.

Debra Heleba is the regional communications specialist at Northeast SARE. Funded by the USDA, Northeast SARE offers competitive grants and sustainable agriculture education to address key issues affecting the sustainability of agriculture throughout the region. Northeast SARE will be accepting applications for its Farmer Grant program this fall for projects starting in spring 2022. More information is available at https://northeast.sare.org/.

Leave a Reply