Another Awesome Superfund Project in Vermont

View of tailing and waste rock capped storage and barren ground next to the north cut. Photo credit: EdwardEMeyer, Wikimedia.org.

By George Harvey

In 1809, the Elizabeth Mine, a source of copper ore, opened in Orange County, Vermont. With the exception of a lapse of a bit over twenty years from 1901 to the 1920s, the mine continued to produce copper for about one and a half centuries.

Originally, Elizabeth Mine was a strip mine. Ore was extracted from two large pits in the ground. In 1886, underground mining was begun. Over its lifetime, the mine produced over 4250 tons of copper. During World War II, it was one of the twenty most important sources of copper in the United States. It went into decline after the war, however, and was finally closed in 1958.

The ore at Elizabeth Mine was of rather low grade, and this meant there was a lot of waste left over from extracting the copper, which was done on site. When the mine closed, that waste remained in a variety of forms, leaching various toxic substances into the west branch of the Ompompanoosuc River, a 25 mile long tributary of the Connecticut River.

Because the toxins were leached by naturally flowing water, largely rainfall, through large piles of waste, the damage would continue to go on until the waste was cleaned up. The Elizabeth Mine was declared a Superfund Site, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources started (VTANR) developing a plan for dealing with the waste in 2000.

Cleanup, an EPA project with work by the Army Corps of Engineers, began in 2010, with an expected cost of $70 million. We might note that the cost of cleanup was about 82 cents for each pound of copper the mine ever produced. But cleanup had to be done, because the site was contaminating the rivers all the way to Long Island Sound.

One thing that can be said about brownfield sites, in general, is that there is not a lot that can be done with them. They cannot be used for parks or farms because of dangers from remaining toxins. In the cases of open pit mines and landfills, the land itself is sufficiently unstable, that it makes no sense to put any sort of structure on it. Nevertheless, such a site can often be used for a utility-scale solar installation.

Elizabeth Mine Solar Farm consisting of 19,990 solar modules of 345 watts. It is expected to generate enough electricity each year for about 1,200 families. Photo courtesy of Weston and Sampson Engineers.

In 2011, Brightfields Development and Wolfe Energy approached the EPA and the VTANR with the idea of developing the Elizabeth Mines Superfund site once remediation was complete. The original partners brought in Greenwood Energy to handle financing. In turn, Greenwood brought in Conti Solar to manage the design and construction. The engineering firm was Weston and Sampson.

Because of the nature of the site, where the ground can settle in time, the solar modules had to be supported by ballasted systems. These were supplied by Solar FlexRack, pre-cast, and moved to the site by trucks. The ballast systems had a total of 19,990 solar modules mounted on them, each of 345 watts. The photovoltaics were manufactured by Hyundai.

Power from the site will be supplied to the utility, Green Mountain Power. Even the task of connecting the site to the grid was not trivial. Four miles of utility power lines had to be put in, and a regional substation had to be upgraded. These upgrades included upgrading service to local subscribers, as well. There also had to be ten miles of optical fiber installed.

The 28-acre site sits on the border between the towns of Strafford and Thetford, Vermont. As a former superfund site, it had little use to anyone. Covered with solar panels, however, it is expected to generate enough energy each year to cover the electricity needs of about 1,200 families.

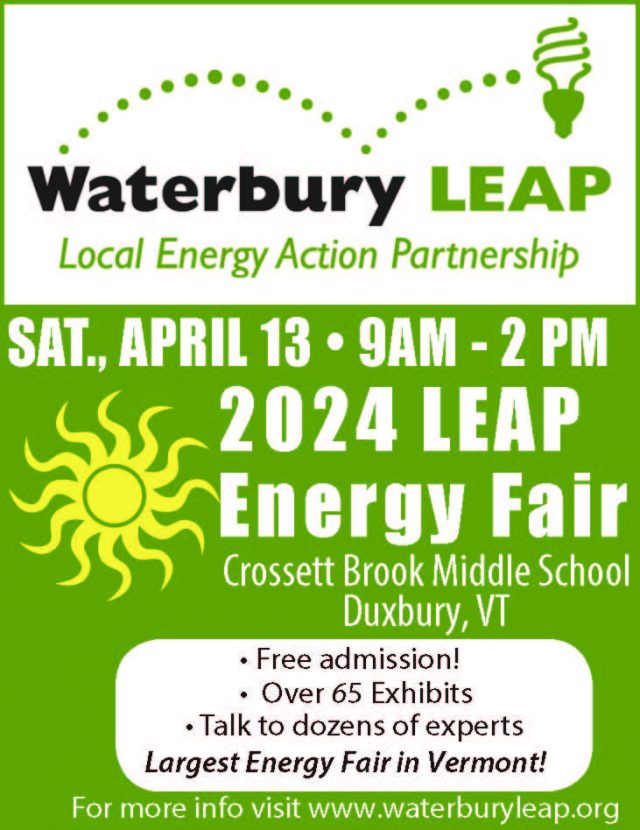

Many Thanks to our Sponsor:

In support of Green Energy Times for

their perseverence to change the world!

Leave a Reply