by George Harvey

In 2010, a new law in Massachusetts enabled community Solarize campaigns. For the first time, there was a policy framework to encourage community efforts to decrease dependency on fossil fuels. Many people could move ahead with long-cherished dreams to have their own power from their own solar systems at their own homes.

The most active community in the state was almost certainly Harvard, a bucolic town about twenty-five miles west of Boston. A number of residents had already thought over installing solar systems, only to be discouraged by the complexity of the process. The Solarize Program simplified the work while providing the advantage of a “bulk buy” to reduce system costs.

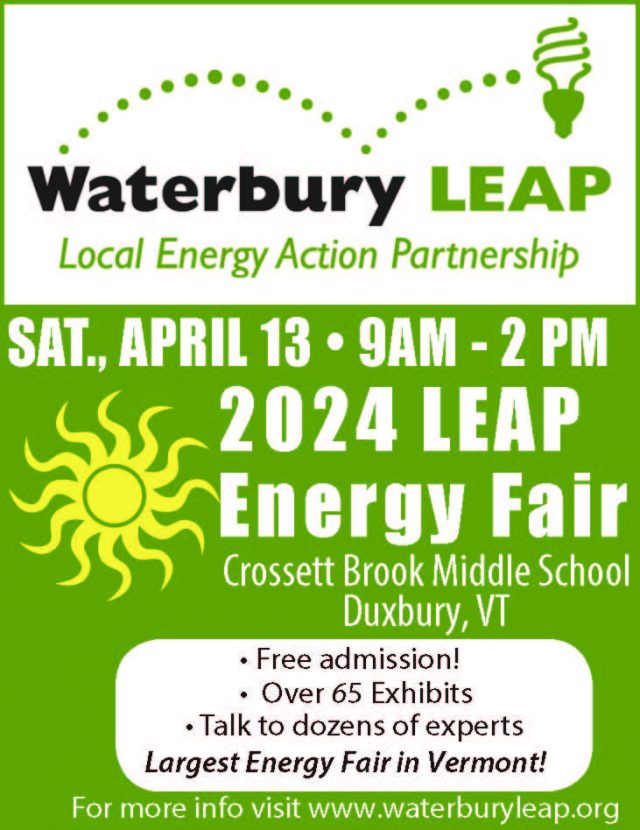

The 550 kW Harvard Community Solar Garden is the first shareholder-owned solar garden in Massachusetts . Photos courtesy of Steven Strong, president of Solar Design Associates.

People soon saw that the Solarize campaign could put the solar dream financially within reach. The campaign came together quickly, as volunteers spread the word, informing people about possibilities and helping sign folks up to get solar systems. Excitement ran high, and the number asking for site evaluations was impressive.

As usual in solar campaigns, many people who wanted systems found their sites were not suitable. Usually the issue was shading caused by anything from trees to dormers and chimneys, but other issues, such as aging roofs can also cause siting problems.

There were about sixty people who wanted to participate in Harvard’s Solarize Program, but could not because of physical siting problems. Unsurprisingly, many of these people were both determined and inventive. The idea that residents could have their solar panels in a common installation was born, likened to a CSA but for harvesting photons.

Today, solar gardens are commonplace, but this was in 2011, the old days. For Harvard, it was a pioneering effort in wholly uncharted territory. Today, it is hard to imagine much going wrong, but in those days, everything imaginable did go wrong, along with many things ranging from unimaginable to inconceivable.

There were no great technical hurdles. Steven Strong of Solar Design Associates provided technical guidance pro bono to the Solarize program and helped guide the group forward, shaping the first shareholder-owned solar garden. The state provided a grant of over $150,000. Problems of policy, politics, personality, and ignorance arose in a situation where there were no established guidelines. Steven Strong openly admits he was naïve about how extensive difficult issues could be.

Before the first town planning board meeting addressing the Harvard Solar Garden, many citizens became immersed in bad information. They had been told solar electric power could create an electromagnetic field that would lead to health issues, and a few believed it, ignoring the utility-supplied electricity already running through their homes. Some were misinformed about the mineral contents of solar panels, and believed that rains would leach toxic materials from the glass panels into the water table. These and similar issues had to be addressed seriously within the context of a public meeting.

Resistance from the town’s zoning and select boards sent the garden advocates on a nearly circular path, as they tried to find a site for the array. Attempts to use agricultural land failed due to zoning, so they tried commercial. This also failed for zoning as solar was not an “allowed use.” Garden advocates were then told that the former town dump was the only place they could site the array. Engineers said this was simply impossible because the dump was in a swamp, subject to differential settlement, and had never been properly closed and capped. However, the select board came to see that project supporters were getting upset. They were reminded that the town had accepted a state grant as a ‘Green Community’ and were obliged to allow solar “as of right” in the town. After a special town meeting, they finally decided commercial land could be used for the solar garden after all. Finding a supportive owner of commercial land in Harvard was a relatively minor challenge .

The town assessors then threatened to tax the solar array as commercial property. That would have severely undermined the financial viability of the project, but circumventing this required an act of the state legislature. A “home rule petition” was guided through the agonizingly slow process of getting to the floors of the Massachusetts House and Senate. Normally such a petition languishes, but two committed local legislators guided it through. The actual vote took only two minutes in each chamber.

The building inspector then provided another hurdle by setting the highest possible permitting fees, but the next issue was even worse. The bank, which had no experience with loans for solar systems, spent over ten thousand dollars on legal fees looking into the project, before turning down the loan. After finding a more progressive bank that liked the idea and became a subscriber, the next step was to get Verizon, the phone company owning the utility poles, and National Grid, the utility that had to install the electric connection, to talk with each other. That process that took almost six months.

The ribbon-cutting event for the Harvard Solar Garden was a time to celebrate.

The people who brought the Harvard Solar Garden together worked within a system that had no idea how to deal with them. Nevertheless, after working on policy issues for two and a half years, the first phase of 250 kilowatts (kWp) was completed in a little under two months, including site preparation. The next phase, bringing the project to 550 kWp, was quicker.

Steven Strong likes to point out that while the Harvard Solar Garden operates like a cooperative it is structured as an limited liability corporation, with the subscribers as the only shareholders. It was the first such solar project, and is still the only truly shareholder-owned one in Massachusetts. He says this is an ideal model because it keeps all the benefits local. “I see the solar garden as the great democratization of electric power,” Strong says. “We need to push, nationwide, for that democratization, to allow everyone access to solar power.

Thanks to the people of Harvard, for their pioneering determination.

Leave a Reply